Iranian Architecture

Architecture in Greater Iran has a continuous history from at least 5000BCE to the present, with characteristic examples distributed over a vast area from Syria to North India and the borders of China, from the Caucasus to Zanzibar. Persian buildings vary from peasant huts to tea houses, and garden pavilions to "some of the most majestic structures the world has ever seen.

Iranian architecture displays great variety, both structural and aesthetic, developing gradually and coherently out of prior traditions and experience. Without sudden innovations, and despite the repeated trauma of invasions and cultural shocks, it has achieved an individuality distinct from that of other Muslim countries. Its paramount virtues are several: a marked feeling for form and scale; structural inventiveness, especially in vault and dome construction; a genius for decoration with a freedom and success not rivaled in any other architecture.

Traditionally, the guiding, formative, motif of Iranian architecture has been its cosmic symbolism by which man is brought into communication and participation with the powers of heaven. This theme, shared by virtually all Asia and persisting even into modern times, not only has given unity and continuity to the architecture of Persia, but has been a primary source of its emotional characters as well.

Traditional Iranian architecture has maintained a continuity that, although frequently shunned by western culture or temporarily diverted by political internal conflicts or foreign intrusion, nonetheless has achieved a style that could hardly be mistaken for any other.

In this architecture, there are no trivial buildings; even garden pavilions have nobility and dignity, and the humblest caravanserais generally have charm. In expressiveness and communicativity, most Persian buildings are lucid-even eloquent. The combination of intensity and simplicity of form provides immediacy, while ornament and, often, subtle proportions reward sustained observation.

Iranian architecture is based on several fundamental characteristics. These are:

• Introversion

• structure

• homogeneous proportions

• anthropomorphism

• symmetry and anti-symmetry

• Minimalism

Overall, the traditional architecture of the Iranian lands throughout the ages can be categorized into the seven following classes or styles ("sabk"):

• Pre-Islamic:

* The Pre-Parsi style : The "Pre parsi style" is a style (sabk) of architecture when categorizing the history of Iranian architecture development.

The oldest remains of architectural elements in the Iranian plateau is the Teppe Zagheh, near Qazvin. Elamite and proto-elamite buildings are also covered within this category.

Other extant examples of this style are Chogha zanbil, Sialk, Shahr-i Sokhta, and Ecbatana.

* The Parsi style : The "Parsi style" is a style (sabk) of architecture when categorizing Iranian architecture development in history.

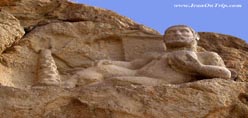

Examples of this style are Pasargad, Persepolis, Mausoleum of Maussollos, Palace of Susa, and Naqsh-e Rustam.

* The Parthian style : The "Parthian style" is a style (sabk) of historical Iranian architecture.

This style of architecture includes designs from the Seleucid, Parthian, and Sassanid eras, reaching its apex of development by the Sassanid period.

Examples of this style are Nysa, Anahita Temple, Khorheh, Hatra, the Ctesiphon vault of Kasra, Bishapur, and the Palace of Ardashir in Ardeshir Khwarreh (Firouzabad).

• Islamic:

* The Khorasani style : The "Khorasani style" is a style (sabk) of architecture when categorizing Iranian architecture development in history.

Examples of this style are Mosque of Nain, Tarikhaneh-i Damghan, and Jame mosque of Isfahan

* The Razi style : The "Razi style" is a style (sabk) of architecture when categorizing Iranian architecture development in history.

Examples of this style are Tomb of Isma'il of Samanid, Gonbad-e Qabus, Kharaqan towers.

* The Azari style : The "Azari style" is a style (sabk) of architecture when categorizing Iranian architecture development in history.

Examples of this style are Soltaniyeh, Arg-i Alishah, Mosque of Varamin, Goharshad Mosque, Bibi Khanum mosque in Samarqand, tomb of Abdas-Samad, Gur-e Amir, Jame mosque of Yazd.

* The Isfahani style : The "Esfahani style" is a style (sabk) of architecture when categorizing Iranian architecture development in history.

Examples of this style are Chehelsotoon, Ali Qapu, Agha Bozorg Mosque, Kashan, the Shah Mosque, and the Sheikh Lotf Allah Mosque.

* The Safavid dynasty were chiefly instrumental in the emergence of this style of architecture, which soon spread to India in what became known as Mughal architecture.

Available building materials dictate major forms in traditional Iranian architecture. Heavy clays, readily available at various places throughout the plateau, have encouraged the development of the most primitive of all building techniques, molded mud, compressed as solidly as possible, and allowed to dry. This technique used in Iran from ancient times has never been completely abandoned. The abundance of heavy plastic earth, in conjunction with a tenacious lime mortar, also facilitated the development of the brick.

Iranian architecture makes use of abundant symbolic geometry, using pure forms such as the circle and square, and plans are based on often symmetrical layouts featuring rectangular courtyards and halls.

Certain design elements of Persian architecture have persisted throughout the history of Iran. The most striking are a marked feeling for scale and a discerning use of simple and massive forms. The consistency of decorative preferences, the high-arched portal set within a recess, columns with bracket capitals, and recurrent types of plan and elevation can also be mentioned. Through the ages, these elements have recurred in completely different types of buildings constructed for various programs and under the patronage of a long succession of rulers.

The columned porch, or talar, seen in the rock-cut tombs near Persepolis, reappear in Sassanid temples, and in late Islamic times it was used as the portico of a palace or mosque, and adapted even to the architecture of roadside tea-houses. Similarly, the gonbad on four arches, so characteristic of Sassanid times, is a still to be found in many cemeteries and Imamzadehs across Iran today. The notion of earthly towers reaching up toward the sky to mingle with the divine towers of heaven lasted through the 19th century, while the interior court and pool, the angled entrance and extensive decoration are ancient but still common features of Iranian architecture.

The pre-Islamic styles draw on 3-4 thousand years of architectural development from various civilizations of the Iranian plateau. The post-Islamic architecture of Iran in turn, draws ideas from its pre-Islamic predecessor, and has geometrical and repetitive forms, as well as surfaces that are richly decorated with glazed tiles, carved stucco, patterned brickwork, floral motifs, and calligraphy.

As such, Iran ranks seventh in the world in terms of possessing historical monuments, museums, and other cultural attractions and is recognized by UNESCO as being one of the cradles of civilization.

Each of the periods of Elamites, Achaemenids, Parthians, and Sassanids were creators of great architecture that over the ages has spread wide and far to other cultures being adopted. Although Iran has suffered its share of destruction, including Alexander The Great's decision to burn Persepolis, there are sufficient remains to form a picture of its classical architecture.

The Achaemenids built on a grand scale. The artists and materials they used were brought in from practically all territories of what was then the largest state in the world. Pasargadae set the standard: its city was laid out in an extensive park with bridges, gardens, colonnaded palaces and open column pavilions. Pasargadae along with Susa and Persepolis expressed the authority of The King of Kings, the staircases of the latter recording in relief sculpture the vast extent of the imperial frontier.

With the emergence of the Parthians and Sassanids there was an appearance of new forms. Parthian innovations fully flowered during the Sassanid period with massive barrel-vaulted chambers, solid masonry domes, and tall columns. This influence was to remain for years to come.

The roundness of the city of Baghdad in the Abbasid era for example, points to its Persian precedents such as Firouzabad in Fars. The two designers who were hired by al-Mansur to plan the city's design were Naubakht, a former Persian Zoroastrian who also determined that the date of the foundation of the city would be astrologically auspicious, and Mashallah, a former Jew from Khorasan.

The ruins of Persepolis, Ctesiphon, Jiroft, Sialk, Pasargadae, Firouzabad, Arg-é Bam, and thousands of other ruins may give us merely a distant glimpse of what contribution Persians made to the art of building.

The fall of the Persian empire to invading Islamic forces ironically led to the creation of remarkable religious buildings in Iran. Arts such as calligraphy, stucco work, mirror work, and mosaic work, became closely tied with architecture in Iran in the new era. Archaeological excavations have provided sufficient documents in support of the impacts of Sasanian architecture on the architecture of the Islamic world.

Advent of Islam in Fran (635 A.D.) gave rise to great upheavals in architecture, and laid the foundations for Islamic architecture all over the world. To be sure, no Persian building from the first two Islamic centuries have survived, but from third center onward, Islamic building flourished rapidly and marvelously expanded during the next centuries.A great surge of building works together with unique decorations and calligraphy appeared in these centuries.

The new chapter which was opened in the Islamic period led to the creation of remarkable religious buildings. Iranian arts such as calligraphy, stucco, mirror work, and mosaic work, became closely tied together in this new era. Islamic architecture and building decoration are among the most beautiful means of expression. Decoration does not play such an important role in any other type of architecture.

The archaeological excavations have provided sufficient documents in support of the impacts of Sasanian architecture on the architecture of Islamic period. According to a classification suggested by Zaki Mohammad Hossain, the fourth period of Iranian architecture (from 15 through 17 Centuries) is the most brilliant period. Various structures such as mosques, mausoleums, bazaars, bridges, and different palaces have mainly survived from this period. In the old Iranian architecture, semi-circular and oval-shaped vaults appeared and Iranians showed their extraordinary skill in making massive domes. Domes can be seen mainly in the structure of bazaars and mosques, and particularly in the historic buildings of Isfahan. Iranian domes are distinguished for their height, proportion of elements, beauty of form, and roundness of the dome stem. The outer surfaces of the domes are mostly mosaic faced, and create a magical view.

According to Dr. D. Huff, a German archaeologist, the dome, similar to Iran itself, is the dominant element in Persian architecture. This statement, applies fully to Iranian architecture; because when one looks at lrano-lslamic buildings, huge halls and massive domes are the first elements which immediately attract one's attention. The art of tile work used to decorate all sorts of ivans, domes, and portals, is so interesting that each part of it seems, to be a magnificent piece of painting.

Professor A.U. Pope, who had carried out extensive studies in ancient Iranian and Islamic buildings, believed: "The supreme Iranian art, in the proper meaning of the word, has always been its architecture. The supremacy of architecture applies to both pre-and post-Islamic periods.

Islamic architectural monuments of Iran are extremely versatile. Different valuable samples of such monuments are already surviving in smaller and larger towns of Iran. One of the richest artistic centers of Iran is the city of Isfahan. In some art works created in Isfahan, such doors, seven famous arts of joinery, gold beating, embossing, lattice work, inlay, raised work, and painting are used at once. Extremely fine doors are decorating various religious buildings in Iran, Najaf, Karbala, Damascus, and other sacred towns of the Islamic world. Even some of these doors are kept in major local and foreign museums because of their high artistic values and decorative arts used in them. Shrine of Imam Reza, 8th Shi'ite Imam at Mashhad, Shrine of Fatemeh the Immaculate (Hazrat-i-Ma'sumeh) at Qum, Shrine of Shah Abdul Azim at Shahr-i-Rey, and Shah-iCheraq Shrine at Shiraz, as well as numerous splendid mosques, open up new vistas of the Islamic art of Iran to the visitors.

Shrine of Imam Reza consists of 33 buildings embodying Iranian Islamic architecture through 5 continuous centuries. Halls, porticos, ivans, minarets, and belfries of religious buildings and mosques have been decorated with a great number of arts such as tile work, inlay, mirror work, stucco carving, stone carving, painting, illumination and muqarnas (honey comb work). Muqarnas is a sort of stalactite work, and an original Islamic design involving various combinations of three-dimensional shapes, corbeling, etc. which was used for the decoration of mosque portals. It can be of terra-cotta, plaster, or tiles.

The value and respect given by Iranians to their religious leaders, have deeply penetrated in their traditional and Islamic architecture. The Iranian Muslim artists have decorated the interior and exterior surfaces of religious buildings, domes, belfries, and mosque minarets with the most beautiful tiles in terms of color and design. During the Islamic period, several palaces, bridges, avenues, and gardens were either built or reconstructed in various towns of Iran, particularly in Isfahan. Historic monuments of the latter town are so numerous that nowadays it is compared to huge museum of art works.

Foreign travelers called it "Half of the World". Sir Jean Chardin (161713) a dependable observer and a French traveler who made journeys to Persia and visited Isfahan during Safavid period, said in 1666 that the town had 164 mosques, 48 madrasas (schools), 182 caravanserais, and 373 baths.

The great maydan (square) at Isfahan called Naqsh-i-Jahan (world image) contains a galaxy of excellent architectural works of Iran. The square is situated in the center of the present city of Isfahan, and has been described as unique by world archaeologists in terms of architectural style, dimensions, and splendor.

No doubt, by the end of 16th century, no such maydan had been constructed neither in Iran, nor in other countries of the world. This unique phenomenon of art and architecture is a creation of experienced and creative Iranian architects.

The most famous architectural works of Maydan Naqsh-i-Jahan are Masjid-i-Shah (now Imam Mosque). Shaykh Lutf' Allah mosque, and the Al Qapu Palace - seat of government - situated in their full splendor at the north end, east and west of maydan, respectively.

The southern side of maydan leads to the great bazaar of Isfahan, which is one of the most attractive and beautiful bazaars of the east, representing the great era of Islamic architecture with its buildings, the maydan and its historic monuments during the Safavid period (1491-1722).

Architectural monuments of Isfahan are known for better in western countries compared to other architectural masterpieces of Iran. They enjoyed a legendary fame in European countries at the time of their construction. Foreign merchants, travelers, and ambassadors have appreciated the beauties of Isfahan in their own languages. During the recent centuries, too, many famous Iranologists and archaeologists have traveled to Iran from all over the world and carried out deeper studies concerning the architectural monuments of Isfahan. As the result of such- studies, numerous books and articles have appeared in connection with the Islamic art of Iran, particularly its architecture.

The Masjid-i-Shah (Imam Mosque), begun in 1612, and, despite Shah Abbas' impatience, under construction until 1638, represents the culmination of a thousand years of mosque building in Persia, with a majesty and splendor which places it among the world's greatest buildings..

In designing and constructing domes, minarets, ivans, halls, Shabistans, and Mihrabs of this mosque, Iranian architects have made use of their utmost degree of taste and artistry. Inscriptions of the mosque have been written on colored tiles by the most famous calligraphers of Safavid period.

The massive dome of the mosque is of double shell type, the highest exterior point of which rises 54m above ground. Its interior and exterior facings are decorated as beautifully as possible with plain and patterned tiles.

The mosque of Shaykh Lutf Allah (1601-28), one of the most beautiful architectural monuments of Iran, is situated on the east side of the Naqsh-i-Jahan square. Designs and colors used in the dome mosaics are among the most elegant designs and colors existing in Iranian architecture.

According to A.U. Pope, there is no weak point in this building. Its plan and design are so strong and attractive. It is a combination of excitement and passion, glorious calm and rest which originates but from religious faith and divine inspiration.

Masjid-i-Jameh (Friday Mosque) is another valuable architectural work of Islamic period displaying experiences of more than nine hundred years of creativity. Thirty various historical inscriptions give details on different architectural structures of the mosque.

Apart from Iranian archaeologists, some European archaeologists like All A.U. Pope, Andre Godard, Myron Smith, etc., have made extensive studies about various architectural aspects and decorations of Masjid-i-Jameh at Isfahan. The result has been several books and specialized scientific articles dealing with the marvelous architecture of this mosque.

The mosque has been restored and changed several times and by several generations of artists and architects. Skillful Iranian tile makers have embellished its walls and vaults with astonishingly beautiful tiles and mosaics. The tiles are decorated with floral designs in arabesque style and phrases from the Holy Quran.

The splendor and architectural beauty of the Iranian mosques belongs to their tile work and artistry of tile workers. Tile making and tile working are among the most spectacular Iranian arts which culminate in the tile work of mosques and historical structures of Iran,

The tile makers of Isfahan, Kashan, and Rey used to be unique master of their trade. Tiles were designed, painted and decorated in various types. Various tiles were used in the embellishment of mosques. Tiles contained floral designs in Arabesque and phrases of the Holy Quran in different Arabian calligraphy known as Sols, Nastaliq, Kufic, etc., all on tiles of deep azure blue or other colors. Tiles used in non-religious buildings were designed and painted with brighter floral and animal, and sometimes human images.

Development of Iranian architecture can be traced also in mosques of other towns such as Masjid-i-Jameh Nayin (mid-tenth century), Masjid-i-Jameh Ardistan (circa 1180), Masjid-i-Jameh Zawareh (1153), Masjid-i-Jameh Golpayegan (12th century), and historical mosques of Tabriz and Yazd.

Stucco is another decorative art of Iranian architecture. The Islamic period architects were unparalleled in the art of stucco.

An outstanding example of stucco fulfilled with extraordinary precision, is observed in the mihrab of Nayin Mosque. The stucco belongs to tenth century A.D. During the 1h century (Seljoogh period:

1000-1157) A.D., majority of mihrabs were decorated with the most beautiful stuccos.

Stone and stucco carvings have played a significant role in the internal and external decorations of Seljoogh buildings, the most remarkable examples of which are the magnificent inscriptions in kufic and nastaliq calligraphy as well as stucco carvings of mosques. The stucco and stone carving techniques of Seljoogh architecture can be observed in the majority of 12th century buildings and monuments. Mihrabs of Masjid-i-Jameh Qazvin (1116 A.D.) and Masjid-i-Jameh Ardistan (1160 A.D.) are extremely valuable examples of stucco carving art. During Seljoogh period, stucco carving was used not only for the decoration of mosques but also for palaces and houses of the nobility, with themes varying from landscapes or hunting scenes of kings accompanied by their courtiers and princes.

Seljoogh decoration techniques was carried further until a certain time when it was replaced by a new technique during Mongol period (1211334 A.D.). The Mongol technique of decoration can be observed in some structures of Azarbaijan. A good sample of Mongol stucco carving is surviving at Hedariya Madrasa (mosque), Qazvin (early twelfth century).

The power and nobility of Mongol stucco carving is probably best exemplified by the mihrab of Masjid-i-Jameh Isfahan built in 1310 AD. during the reign of Ulyaitu and known as the Uljaitu Mihrab with the archaeologists.

In addition to religious structures, there are a number of old houses in various towns of Iran which were decorated with unique stucco carvings, already being preserved as historic buildings.

Suitability of brick for plaster facing, had been the main reason for the spread of the finest stucco carvings in the decoration of Iranian architectural buildings.

Stuccos using carving, molding and painting, constitute one of the main decorative elements of Iranian architecture, and have a long history of development. Types of stucco decoration have been tested by Iranian architects since approximately 2000 years ago.

Mirror work is another decorative element of Iranian structures during Islamic period. The finest examples of skillfully fulfilled mirror work can be seen in the religious buildings of Mashhad, Shiraz, Qum, and Rey. The technique has been used in palaces and magnificent traditional houses as well, and follows architectural elements such as domes, minarets, and towers in terms of significance.

Minaret is a slender and tall structure (tower) constructed on both sides of a mosque dome or domes of religious buildings. Some minarets are constructed independently. The oldest known Iranian minaret, Mil-i-Ajdaha, was built during Parthian period in Nourabad Mamasani, Fars Province, to guide the caravans. In remote past, minarets were used as guide posts. Caravans moving on the vast Iranian plateau, could find their routes in endless deserts and plains only by mean of such minarets.

Minarets were signs of nearly caravanserais, towns, or inns. Minarets built along Persian Gull' coastline and main ports, served as light houses. Land caravan and ship arrivals or departures, and possible attacks by pirates were signaled through these minarets by fire or smoke.

In Islamic period, minarets appeared shortly after mosques. Mosque minarets had mostly tile facings, while a grate number of minarets were built using brick alone. Their brick decorations were extremely fine and artistic.

The finest and tallest Iranian minarets are standing in Isfahan and certain towns in Kavir. Brick work as decorative art of Iranian architecture developed to its highest triumph in many ancient structures, towers, and minarets.

In his description of the Iranian artists' brick work, Sir Edwin Lutyer said: One should never talk of Iranian brick work, but mainly of the magic of Iranian brick work. Endless variety of arches and cross vaults with their exciting shapes, all stem from the artistic taste of Iranian brick work architects.

The quality and skills of Iranian brick work architects can be distinguished in monuments they created and left for us. Altogether 12 slender and very tall minarets survive in Isfahan region, which are unique in their architecture and beauty. Little has remained of minarets built of mud brick.

Construction date of some brick minarets are given on their inscriptions: Damaqan minaret in 1209 A. D., Isfahan Chehel Dokhtaran Minaret in 1107 A.D., and Isfahan Qushkhaneh Minaret in 15th century A.D.

Unique architecture and first clan brick and mortar used in the construction of minarets have resulted in their surviving after 9 centuries in the earthquake prone land of Iran.

Huge brick tower construction represents another creative aspect of Iranian architecture. Gunbad-i-Qabus is one of the greatest and most beautiful brick towers of Iran built approximately thousand years ago, which stands in perfectly good condition. Under the shadow of the eastern Alborz mountains, facing the vastness of Asian steppes, stands in stark majesty a supreme architectural masterpiece: The Gunbad-i-Qabus, the tomb of Qabus-ibn-Washmgir. It rises a full 167 feet, with another 35 feet or so underground. It was built in 1006 A.D. and is the earliest and most expressive of a series of some fifty monumental towers still standing. Tuqrol Tower near Rey (1139 A.D.) and Bistam Tower (1314 A. D.) are among such towers, each representing a masterpiece of architecture and brick work.

Palaces and gardens of Islamic period introduce us to other aspects of Iranian architecture. Because of the multiplicity of such works and monuments, we give only a few examples here.

The Chehel Sutun palace at lsfahan stands amid a garden called Jahan Nama. It was built in 16 century A.D. during the reign of Safavids. The wooden columns of the palace are placed on stone plinths. The ivan ceiling has been decorated by fine wooden frames of different geometrical shapes. A vast water pond was built immediately in front of the building which gives a mirror-like image of it.

The interior of the palace is covered with beautiful miniature paintings which portray the wars and other ceremonial receptions of Safavid kings. Here one could see the finest paintings of Safavid period. Mirror work designs and latticed windows too, are unique in themselves.

Ah Qapu palace at Naqshi-i-Jahan square, Isfahan is another architectural monument of Safavid period built in six stories. It contains various masterpieces of stuccos and murals. Chardin, who visited the palace during Safavid period, described it as the greatest palace to be found in any capital city. The sixth floor was used for Safavid kings' official receptions. The palace is also unique in terms of its stuccos, murals, rooms, and halls.

Altogether 6 palaces and 34 historical gardens had been built in Isfahan, a number of which are serving today and the rest have disappeared through the ages. The Iranian architecture can be further traced in historical and famous bazaars of great towns of Iran. These bazaars have enjoyed a great reputation among Europeans travelers and merchants.

]The bazaars, known as Eastern Bazaars, apart from being centers of commercial and civic activity were mostly surrounded by public facilities such as the mosques, baths, and caravanserais to meet the requirements of travelers, merchants, and nearly inhabitants. The handsomest traditional and historical bazaars of Iran built in Isfahan, Shiraz, Tabriz, Yazd, Mashhad, and some other towns, are highly important in terms of structure and texture.

In introducing Iranian architecture, one should never overlook the architectural techniques used in the construction of madrasas, baths, and historical caravanserais, a number of the most significant examples of which have survived until our day. Examples of historical baths of the country have already been changed into anthropological museums, with the intention of being well preserved as well.

Architectural monuments and buildings of older times remaining on the vast exauses of Iranian Kavir (desert), too, have always attracted attention of archaeologists and aestheticians. Inhabitants of Kavir have constructed various settlements villages, 102 and towns in margins of Kavir, which give a clear picture of their original architecture and arts. These buildings, apart from being strong in structure, brought about the best and most bearable conditions of living in extremely dry and hot weather of Kavir. Necessity of living in the margins of dry and arid Kavir, and existence of a native art, red to the rise of Kavir architecture in Iran.

According to the archaeological researches carried out so far, the oldest Kavir towns of the world have been built in the margins of Iranian Kavirs.

Yazd, the town of graceful high rising Badgirs (wind towers), is one of the oldest Kavir towns of Iran. The Islamic and traditional architectural monuments existing in this town are extremely versatile.

Badgirs and great Anbars (water stores) of Kavir are among the most interesting architectural developments of Iran. Badgirs were invented in Yazd to cool the people's residences many centuries ago. In other words, they are traditional coolers of Yazd. Architects of Kavir towns have employed the wind energy in order to overcome the unbearable hot weather of Kavir.

Badgirs are inventions of unknown architects whose creative imaginations and taste developed to the highest peaks in architecture. Most houses in Kavir are equipped with Badgir which brings cool air into large rooms and halls in hottest days of summer.

Considering the rarity of water in Kavir regions, people have devised ab-anbars (water stores) as water storages. There is an interesting technique for the construction of anbars in Yazd. One of the most valuable and well-preserved ab-anbars in this town is the one with six huge badgirs used to cool its water. Several examples of badgirs and anbars survive in Kavir towns of Iran.

Iranian architecture at Kavir towns is not limited to the construction of ab-anbars and badgirs, but its main importance lies in house building and city planning. Another manifestation of Iranian architecture in Kavir lands is the construction of Quanat (underground water channel). It consists of a series of wells connected to each other through an underground channel, carrying water from underground depths to its surface. Excavation of quanat presupposed mastery of certain techniques of which only Iranians were fully aware.

Heroclotus writes that Iranians were inventors of quanat. "Iranians were the first nation to carry water from underground channels, to the surface. They were inventors of quanat. Iranian architects have also created extremely valuable monuments in areas such as water and irrigation, dams, canals, and bridges or rivers. The Soviet archaeologists discovered remnants of one of the oldest irrigation canals of the world near the town of Van urkey) which was constructed by the Urartu people in the late 9th century A.D. A cuneiform inscription unearthed from the rubble walls of the canal describes how it was built.

Excavation of Suez Canal between the Nile river and the Red Sea during the reign of Achaemenids was carried out under the supervision and initiation of Iranian engineers and architects. In the vicinity of the canal a stone inscription was discovered from the time of the Achaemenid king Darius I together with an account of how the canal was constructed.

The Athos canal in Greece, too, had been another masterpiece of Iranian architecture. Remnants of the canal stand up to this day.

Numerous bridges and dams had been built during the Achaemenid and Sasanian period in Provinces of Fars and Khuzistan, as well as Mesopotamia. Some of these monuments are standing even today.

Shushtar dam on Karun River, is a dam building masterpiece from Sasanian period in Khuzistan. Dam building techniques continued even during the Islamic period in Iran. Many pre-Islamic dams were repaired by Muslim engineers of Iran, and they applied their own innovation in the construction of newer dams and bridges. Arch dams and diversion canals were first built by Iranian engineers and architects on various rivers. Their methods are used in the construction of the greatest dams of the world even today.

The oldest bridge the remnants of which have survived to our day, is the one built by Urartu people on Araxes River, North West Iran. It was built in 8th century BC.

An example of the most magnificent bridges of Iran are standing in absolutely good conditions in the city of Isfahan. Zayandeh Rud is the greatest river flowing into central plateau of Iran. It flows through the city of Isfahan dividing it into two north south pans. Twelve samples of historic bridges built from Sasanian through Safavid periods stand on it even today. Shahristan bridge is the oldest of those bridges with a minimum history of one thousand years, which belongs to Sasanian period. There are two other world-famous complex bridges built during the Safavid period: (1) Allahverdi Khan or 33-span bridge, which is 360m long and 14m wide, It has 33 spans, and was built by the artful engineers of Isfahan in 1602 A. D.; and (2) Khadlu bridge (in two stories) built during the reign of Shah Abbas II, serving both as a bridge and a dam. It is one of the most elaborate combined bridges of the world, 133.5m in length and 12m in width. It can be changed into a temporary dam by blocking its spans. Wide and thick timbers (stop - logs) had been prepared to be used for this purpose and create a beautiful reservoir on one side of the bridge. The second floor, constructed on the main spans, includes its most fascinating feature, i.e., the pavilions set into its width called "Princes Pariours" and once decorated with faience stucco carvings, and inscriptions. The main parlor was used for the king's receptions and festivals. In terms of architectural style, it is unique all over the world. Majesty and splendor of the historic bridges of Isfahan are vivid manifestations of the creativity of Iranian architects.

The endless variety of architectural monuments in Iran shows that Iranian architects enjoyed highly valuable creativities and experiences in various fields. Despite intervals due to wars, military expeditions, and foreign offensives, Iranian architecture has continued to develop and flourish through the ages. Artists have enriched their previous styles and methods and built on them. Although temporarily influenced by foreign art styles, they proved capable of dissolving such influences in their own arts and creating new forms of Iranian art, even influencing the architecture of other countries.

Architecture in Iran has a continuous history of more than 6,000 years, from at least 5,000 BC to the present, with characteristic examples distributed over a vast area from Syria to North India and the borders of China, from the Caucausus to Zanzibar. Iranian architecture has manifested its own particular characteristics and originality throughout its prolonged history. It was based on a multi-thousand years of experience which, according to A.U. Pope, was popular. Despite being at the service of kings and rulers the main agents of Iranian architecture were artists arising from among the people.

Religious beliefs, particularly during the Islamic period, played a decisive role in giving birth to the majority of Iranian architectural monuments.

Faith, thinking, and creativity were three elements out of which rose Iranian architecture.

Contemporary architecture in Iran begins with the advent of the first Pahlavi period in the early 1920s. Some designers, such as Andre Godard, created works, such as the National Museum of Iran that were reminiscent of Iran's historical architectural heritage. Others, made an effort to merge the traditional elements with modern designs in their works. The Tehran University main campus is one such example. And yet, others such as Heydar Ghiai and Houshang Seyhoun tried creating completely original works that were independent of any precedental influences.

Major construction projects are undergoing all around Iran. Borj-e Milad (or Milad Tower) is the tallest tower in Iran and is the fourth tallest tower in the world. The Flower of the East Development Project is the biggest project on Kish Island in the Persian Gulf. The project, includes a '7-star' and two '5-star' hotels, three residential areas, villas and apartment complexes, coffee shops, luxury showrooms and stores, sports facilities and marina.

Persian architects were a highly sought after stock in the old days, before the advent of Modern Architecture. For example, Ostad Isa Shirazi is most often credited as the chief architect (or plan drawer) of Taj Mahal. These artisans were also highly instrumental in the designs of such edifices as Afghanistan's Minaret of Jam, The Sultaniyeh Dome, or Tamerlane's tomb in Samarkand, among many others.

.....

.....

.....

.jpg)